As an endocrinologist, I have often cautioned about the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing fluid, drilling muds, and acidizing solutions — based in part on PSE’s research findings on the dangers these chemicals pose, and in part on concerns that there is much we don’t know.

There is no legal obligation for drilling contractors or their energy-company employers to disclose the chemicals they use, and listings that do exist often are not fully transparent about all the components of a substance. Companies commonly say that an effective blend of chemicals gives them a competitive advantage over rivals and thus a blend’s contents should remain a trade secret. Because Congress exempted unconventional fossil fuel extraction from many U.S. federal environmental regulations in the 2005 Energy Policy Act, the public is often dependent on an industry that is stingy with information when an accident happens and people are exposed or contaminated.

A May 2017 case study of a poisoning incident is a cogent and convincing illustration of the dangers posed when chemical contamination incidents occur and our access to knowledge of those chemical constituents is limited. In “A Methanol Intoxication Outbreak From Recreational Ingestion of Fracking Fluid,” published in the May 2017 edition of the American Journal of Kidney Disease, Canadian nephrologist David Collister presents ten cases of self-poisoning with a product called “Frosted White” that is used in making hydraulic fracturing fluid.

In one highlighted case:

“A 28-year-old First Nations man … presented to a nursing station in remote Northern Manitoba, Canada, with nausea and vomiting. He did not report any other symptoms. Approximately 24 hours prior to presentation, the man had recreationally consumed an undisclosed amount of ‘Frosted White’ with friends. The substance was later confirmed to be a fracking mining fluid consisting of 85% ethanol, 13.7% methanol, and 0.85% acetate. A toxic alcohol ingestion was suspected, and after consultation with a toxicologist, the patient was transferred by air ambulance to a tertiary-care facility with [High Dependency] facilities in Winnipeg.”

Based on its components, Frosted White is likely used as a surfactant, a common fracking chemical that adjusts the surface tension of liquids to help separate oil from rock. The authors do not reference how they identified the ingredients in this product, and I have been unable to find its material safety data sheet — a disclosure document required for toxic substances. Presumably the treating physicians contacted the manufacturer or perhaps the drilling company that employed the men who got sick. Without disclosure information, we have to take on trust that the fluid’s contents are as stated, and that there are no other undisclosed chemicals.

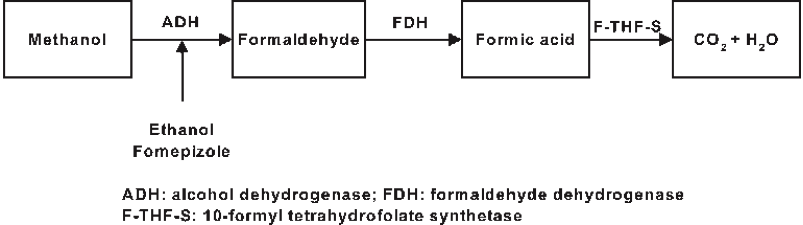

Methanol is a well-studied toxic substance that can cause severe consequences when a significant amount is absorbed. Methanol can interact with an enzyme in the body and convert to formaldehyde, which, if ingested, can cause an acute, severe increase in blood acidity (acidosis), which causes the body to produce formic acid, which in turn may result in lactic acid build-up, shock, and organ failure, including kidney failure and death.

There are two antidotes to methanol poisoning. The formation of formaldehyde and formic acid can be prevented by 1) an IV infusion of ethanol or 2) by the medication fomepizole, which inhibits an enzyme that interacts with methanol to form these toxins. Regrettably, by the time victims of methanol poisoning become aware of the problem, they often already have severe acidosis and end-stage organ damage.

Above: Methanol produces toxicity by reacting to form formaldehyde and formic acid, resulting in carbon dioxide concentrations that make blood highly acidic and lead to organ damage. From Wiki Tox.

Fortunately, the man in the article was airlifted to a University of Manitoba care center in Winnipeg, where he received state-of-the-art treatment from a multidisciplinary team that included emergency room physicians, nephrologists, and internal medicine specialists in an intensive care setting. He had infusions of fomepizole, folinic acid, sodium bicarbonate for the acidosis and required kidney dialysis. He made a full recovery and was discharged.

By tracing the admitted patients’ contacts, the care team identified nine other people who drank Frosted White and expedited their transport to the Manitoba care facility. Three patients required fomepizole therapy, two of whom were sick enough to be treated with kidney dialysis.

The authors focus on why all ten poison victims had a good outcome, including the possibility the ethanol in the Frosted White may have mitigated the severity of the methanol’s adverse effects. They state that without the team approach and the medical resources required, or if more subjects had drunk the chemical mix, there could well have been a disastrous outcome. While the authors outline their successful therapeutic regimen, what they don’t mention is the high cost of this treatment. The fomepizole alone likely costs more than $4,000 per treatment. Add the expense of airlifting, emergency department and ICU time, dialysis, and staffing costs, and the collective economic cost of all ten cases was likely very high.

Key issues that spring from the case history

Data from the case history, including the treatment costs, raise several critical issues.

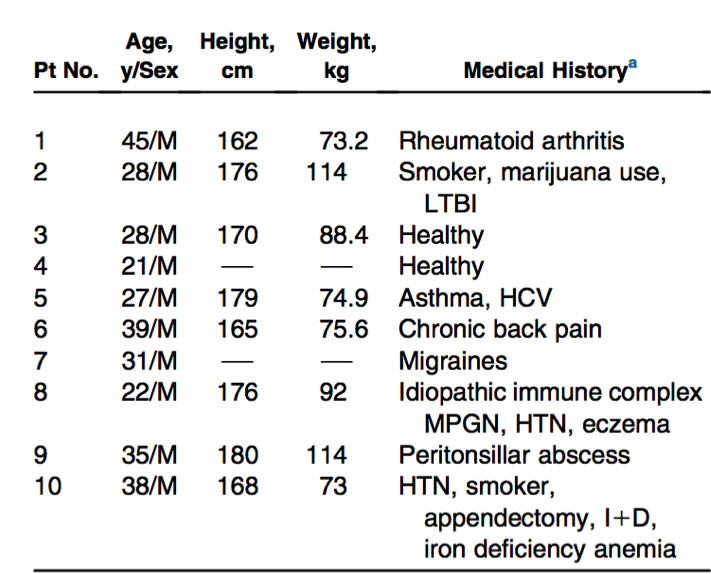

Equity: The communities typically affected — including rural, First Nation, and impoverished individuals — already have high burdens of disease, as shown in Table 1 (right). The considerable comorbidities, that is, existing health issues, for a group of young men, bear out this public health statistic and can complicate medical management of poisoning. Such communities are vulnerable because of their passive exposure to industrial pollution, but also because alienation and impoverishment can lead inhabitants of these areas to participate in risky behavior. The remoteness of many of the areas where unconventional gas extraction takes place and the lack of adequate medical facilities nearby compounds the disadvantages these communities already experience.

Transparency: Frosted White is not a product we can learn about readily online. The name itself sounds more like a cocktail than an additive to hydraulic fracturing fluid. It is not clear whether the “acetate” ingredient listed by the authors means acetic acid or a salt, which may be toxic in its own right, yet the industry is not obligated to name all chemical ingredients. This case illustrates that transparency is a matter of medical necessity.

Practical toxicology: Clearly, the ethanol content of this fluid made it appealing to the poison victims. However, accidental exposures can occur in different contexts and through different pathways. Gas field workers may be exposed to chemical products through inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact. Others may be contaminated through spills or leaks. Often, the concentrations of these chemicals may be much lower than in the case study. “The dose makes the poison” is one of the axioms of toxicology — and that if you know the biological effects of high concentrations of the toxicant, then you can likely predict the effects of lower concentrations. However, it is apparent to me as an endocrinologist that these rules don’t always apply. In my area of biology, much lower concentrations of certain endocrine-disrupting fracking chemicals have their maximum activity at extremely low concentrations — an impact that is not predictable from their toxicity profile. Thus, not only are there a variety of possible exposure pathways to these chemicals, but some exposures may be inconspicuous to primary care providers.

Externalized costs: I would like to see an economic analysis of the total costs of this limited mass- poisoning event. Clearly, it was expensive and the costs of an industry-caused event were externalized to Canada’s healthcare system. The incident suggests that it’s time for the industry to create escrow funds to pay for the unanticipated health effects of such chemical exposure, especially given that it is most likely to affect those in society who are least able to afford care.

Case reports are valuable means to document important but hidden health problems. I applaud the authors of this paper, both for taking such excellent care of these patients and also for taking the time to inform the medical profession of the potential for exposure to toxic levels of chemicals from products used in hydraulic fracturing fluids. I also believe that the details of the report underscore serious existing questions connected to chemical use in fracking — regarding both the potential negative medical outcomes that can result from a lack of information about toxic substances, and the multifaceted costs to society when those potentialities result in real-life consequences.