Meet Karan Shetty, M. ESM a Clean Energy Transition Scientist at PSE Healthy Energy whose research is showing policymakers the true cost of burning fossil fuels and helping communities advocate for clean air. .

Q: What do you do here at PSE Healthy Energy?

A: I’m a Clean Energy Transition Scientist – I look at air pollution as it pertains to public health impacts, as well as energy affordability. I’ve been at PSE for four years, and I’ve worked on a lot of different initiatives, looking at health impacts of power plants, polluting industries, and studying air quality regionally with air monitors to point to different sources of pollution.

Q: How did you get into this area of expertise?

A: In high school and college, I became passionate about climate change. I saw it as the issue for my generation and future generations. And I became interested in renewable energy; how to use technology to save the planet and address inequities in our current systems. There are certain communities that face disproportionate burden from our current fossil fuel infrastructure: low income communities, rural communities, communities of color, and so on. I wanted to pursue a career addressing those problems.

I have a bachelor’s in science and environmental science from UCLA, and a master’s in environmental science with a focus on climate and energy from UC Santa Barbara. So I’m University of California through and through!

Q: What is something that you love about your work here at PSE Healthy Energy?

A: We’re at this unique intersection of community, policy makers, scientists, energy, environmental justice, energy justice, and affordability. It feels like we’re on the cutting edge of something every day.

Q: Where do you find beauty and inspiration in your work?

A: My work helps to retire polluting facilities early. That creates a measurable air quality improvement, improves public health for communities, and decreases greenhouse gas emissions. The direct impact is what keeps me going.

Q: What was your most exciting day at PSE?

A: The state of Minnesota was planning the next 15 years of their electricity procurement and there was an opportunity to retire some aging coal and natural gas plants early in favor of installing more renewables like solar and wind and battery storage.

We looked at the health damages from the air pollution from these power plants–particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, nitrogen oxide, sulfur dioxide, and so on. This pollution increases rates of asthma, cardiovascular disease, and heart attacks in communities that are adjacent or downwind.

So we did this health impacts analysis, packaged it with analyses by other organizations, and provided them to the state of Minnesota. A few months later the state approved a plan to retire some of the power plants early, and replace them with renewable energy. That was huge. I thought, “Wow. They’re actually taking our recommendation!” And that was not our only victory. We’ve had quite a few since then.

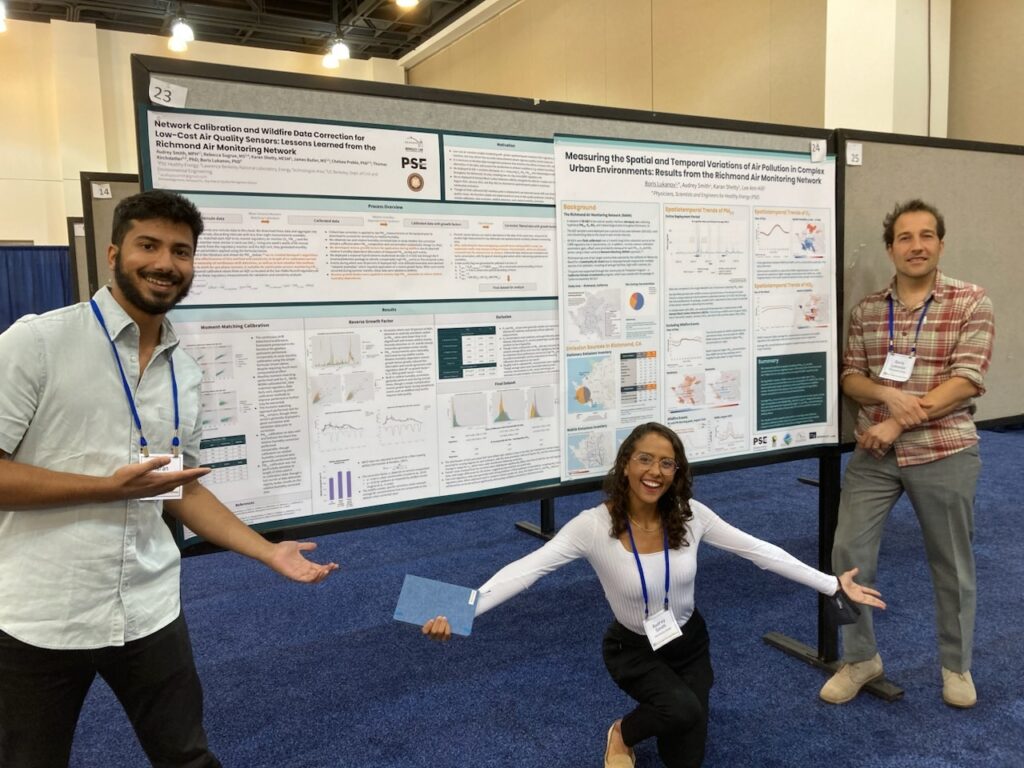

Karan Shetty (left) presents his research on air quality in Richmond, California with PSE colleagues Audrey Amezcua-Smith and Boris Lukanov. Photo courtesy of Karan Shetty.

Q: Do you ever go into the field to collect data?

A: Usually no, but I worked on an air monitoring project in Richmond, which is a city of about 100,000 north of San Francisco and Oakland in the Bay Area that has a lot of environmental burdens. There are three major highways that surround the community. There’s a refinery, a coal train terminal, a landfill, and a bunch of other polluting industries in the area. So PSE set up around 50 low-cost air sensors all over the city to track pollution trends.

Our work helps these communities put concrete numbers behind things they may have felt for a long time, and numbers can be persuasive to policymakers who have the power to make the changes to protect public health.

I’m from the Bay Area, so it was nice to get out from behind my screen looking at data sets and statistics, and talk to fellow citizens. We’d talk about the pollution, about the plumes from the refinery and the smells in the air. My nose was burning a little bit. It was clear what we were trying to solve. Being there added a level of gravity.

Q: Can you give an example of one of the projects you’re working on now?

A: We’re looking at air pollution trends in Contra Costa County. In this case, we’re tracking PM2.5 which is particulate matter that’s smaller than a human hair in terms of width. It can easily get into your lung tissue. It’s dangerous, and it’s emitted from combustion processes and burning fossil fuels – including gasoline and diesel.

We’re looking at air pollution trends; monthly trends, hourly trends, and we see the trends align with traffic. For example from 6 to 10 am there’s a spike in particulate matter emissions, and then it comes down a little bit after that. Then from 2 to 7 pm there’s another spike when everyone’s driving home. And at night it settles down again.

We also look at spatial trends to understand where the pollution is worst. In the previous Richmond air monitoring study, we saw that the monitors by the highways, like I-80, for instance, recorded higher particulate matter levels. The spikes were more prominent, whereas a monitor in a wealthier community up in the hills were not as dramatic. That’s the kind of data I’ll be analyzing right after this interview for this project as well.

Q: Do you think growing up in the Bay Area influenced your career path at all?

A: I think so. There are lots of regional preserves and parks around here. My parents took us to Yosemite and Big Sur and Lake Tahoe, and those are just the most fantastical landscapes imaginable, right? So that fostered my love for the outdoors and the world. As a kid, I’d be out there hiking and exploring. I always envisioned myself like those old school biologists. You know, they’d go bushwhacking to find some rare plants or animals or something like that. And I would do my own version of that in a local park. I’d dig up something and think it was a fossil.

I grew up in San Jose, the heart of Silicon Valley. When I was a child, San Jose was very sleepy, and now you’ve got all these tech giants there. I think there is a way to use technology to help the climate crisis. We can make solar panels and advance the technology for renewable energy or batteries so that they are better than fossil fuels. I grew up with a mindset that technology can help solve problems. While I’m not fully on this train, it’s part of the environment I’ve marinated in so it does influence my thinking.

Therefore I was inspired to pursue something related to environmental science, and to focus on renewable energy as a component of that.

Hiking in the Mt. Baker Wilderness with Mt. Shuksan pictured in the background. Dog clearly having a great time in the snow. Photo credit: Craig Norrie

Q: Do you have hobbies?

A: I do, and they drain my bank account. I love playing music. I mainly play guitar and drums. I can screw around on the keyboard or bass, too. Sometimes I like playing with other people, like jam band style, but most of the time, just by myself. It’s therapeutic to unplug and play guitar.

I’m also big into the outdoors, backpacking, and rock climbing. Now I live in Washington State so I’m getting into mountaineering and snowboarding. I was up in the Sierras a lot in California, now the Cascades here in Washington. It would be cool to bring the guitar up on top of a mountain or something and combine those hobbies.

I’m going to sound like an old person, but with phones and notifications and Slack messages and emails and overwhelming news headlines and every 12 hours it seems like something crazy is happening, it’s good to be outside and not have cell service. To just go out there for a few days, be under glaciated peaks and auroras, and come back dirty and happy.

Q: What would you tell young people who are considering a career in scientific research?

A: This is a long fight and there are a lot of opportunities. So keep your networks open and be flexible. We’re in pretty uncertain times at the moment, but again, this is a long game. Companies are looking for sustainability professionals, as are state governments. Don’t be discouraged. Keep moving forward, because this work is really important.

Q: Can you talk about a science project from your childhood that you loved?

A: In high school I volunteered with a local creek restoration ecology project through the city government. They had me go down to different sites along the Guadalupe River and collect water samples to test the pH, the turbidity, and test for contaminants or pollutants. If I found something we’d triangulate the source. The contaminant wasn’t up there, but we found it down here. So what happened between there and here?

It’s the first time I was doing real environmental science and I loved it. It merged that childhood sense of exploration with actual science. Going out into the mud, into the water, into the woods, and collecting samples. It wasn’t super complicated, but it captured my imagination, and it helped put me on this path.

Q: When did you know that you wanted to pursue a career in research?

A: It wasn’t until I started at PSE, actually. Corporate sustainability was my focus for a while. I was helping big companies with their carbon emissions reductions initiatives, or making the case for installing solar on their facilities. I was used to working within short time frames and getting through projects quickly. The mindset was “we have a short window to finish these projects, so let’s be quick but accurate.”

At PSE the mindset is, “We need to examine a bunch of different components and look at this in many different ways.” And sometimes we find things when we examine something under a different light. That’s a different way of thinking. It’s been interesting over the past four years, adjusting from rapid-fire “gotta get this done” to “we should really explore multiple avenues here,” so that’s been really fun.

Snowboarding at Crystal Mountain with Mt Rainier looming in the background. Photo courtesy of Karan Shetty.